I’ve been thinking about the wisdom that has shaped much of my life. I’m grateful for some of it, to be sure. There’s been a lot more that I’ve had to intentionally dismantle and deconstruct.

I was raised in the church. Both consciously and subconsciously it inferred, offered, and proclaimed Wisdom – as an institution, within its sacred text, because of its God. And not just a wisdom, the wisdom. It was the only wisdom that I was to rely on, turn to, and build my life upon. I was dutiful. I was obedient. I was disciplined. And to be fair, it was this wisdom to which I turned, on which I relied, in which I took solace. The darker side was also true: when I didn’t turn to it, rely on it, or took solace anywhere else, I felt vast shame and guilt.

But it wasn’t just the church, religion, or God as wisdom source – it was men. (White) men were seen as the experts, the holders of authority, the ones I could and should trust. In completely transparency, for a very long time, I rarely-if-ever thought to consider anything else! They had the answers. And because that was so obvious, it was just as obvious that I did not have answers – or wisdom; that my thoughts could not be trusted, that I could not, should not trust myself.

Then there was academia. It would have never crossed my mind to question why all of the things I was learning were from (more) white men. Yes, I had a few women teachers along the way, but they were instructing me from textbooks written by white men. Even in college, as a Business and Communications major, everything I learned was from a man’s perspective, man-as-wisdom. I didn’t question a bit of it. I appreciated what I was learning. I took it in as gospel.

By the time I got to my Masters Degree (with a nearly-20-year break in the middle) very little had changed. The professors and authors were still almost exclusively white men – in my studies of both theology and therapy (especially theology). But it was also during this time that things began to shift. I took a class called Feminist Critique (taught by a visiting professor who was a woman and only assigned texts written by women) that opened me up to a wisdom that made me really, really angry. She systematically revealed the white/male lens everywhere, influencing everything. And that lens was not mine.

At about the same time, probably not at all coincidentally, I began to experiment with the interpretation of women’s ancient, sacred stories through a non-male lens, through a woman’s lens, through a feminist lens, through my lens in order to pull forth something different, anything different. And it was this effort that became a practice that became my everything that enabled me to find, hear, and actually trust my own wisdom. For the first time.

A few weeks back, I woke up in the middle of the night and typed a text to myself – just so I wouldn’t forget the thought that was keeping me from sleep:

We need sources of wisdom that are distinctly feminine. Only they can mirror our experience in ways that allow the wisdom to actually land, to be relevant, to support and strengthen us.

I was pretty happy to see that text waiting for me the next morning.

I’m not opposed to the wisdom of men (well, maybe a little). What I want, though, is the wisdom of women – not in opposition, but as obvious choice.

Without such, it’s no wonder we walk through our lives doubting ourselves, not trusting our intuition, flailing in relationships, putting others ahead of ourselves, tamping down our desires, and wallowing in (often) self-inflicted shame. Everything we learn is not who WE are. Everything we compare ourselves to is not who WE are. This is the patriarchy, of course; the water we swim in, the air we breath, its insipid presence in everything we do, think, and feel.

But…

If we had feminine sources of wisdom – and saw them as reliable, trustworthy, honorable, valuable – we would have a template through which to understand ourselves that syncs with who we most closely are, who we most closely resemble, how we most often act, think, and feel.

Imagine it for a moment.

If I had grown up in a goddess-worshipping coven, it would have been normal for me to trust my body, to eschew anything that smacked of self-contempt, to always look within for answers, comfort, and strength. Even if I don’t take it to that lovely extreme, let’s say I grew up in a Christian home, attending church, going to Bible studies, but everything was focused on women. At church I would have heard stories that were not about a woman’s sin or shame; rather, their magnificence and strength and power. I would have never heard a single message – spoken, assumed, written, or preached – that told me I should be more submissive or more humble or more obedient; rather, I would have been extolled and encouraged to trust my voice, my heart, and yes, my wisdom. I would have grown up reading books written by women, novels about women (written by women), and even if my teachers and professors had remained mostly white men, that input would have been consistently “countered” by the reminder that at the end of the day, what I thought mattered. When I watched TV or read Seventeen magazine, I would not have been inundated by women’s objectification; instead, I would have known and understood that women’s bodies are our own, that they matter, that they are beautiful and perfect – in every way, shape, and form. And I would have been very clear that attracting me was the end-all, be-all – not attracting a boy, a man, or a prince. Can you even imagine?

We need sources of wisdom that are distinctly feminine. Only they can mirror our experience in ways that allow the wisdom to actually land, to be relevant, to support and strengthen us.

This wisdom allows us to see ourselves in the mirror, to listen to the voice within that not only makes sense, but is 100% true and right. This wisdom teaches us to trust ourselves – which leads to agency and power – which leads to doing the unexpected thing, to rising up, to speaking out, to resisting anyone who tells us anything different – which leads to a disallowing of violence because of race or sexuality or difference of any kind, sickening entitlement because of gender or power, and ignorance based not in wisdom, but foolishness!

So find that wisdom. Be that wisdom. Be that wise. It’s all within you. It always has been – for generations and generations, from the beginning of time. And it’s all yours to offer us. Imagine the world you’ll change, create, and birth along the way.

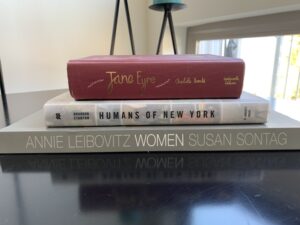

Here’s an example: three books stacked together in my home:

Here’s an example: three books stacked together in my home: